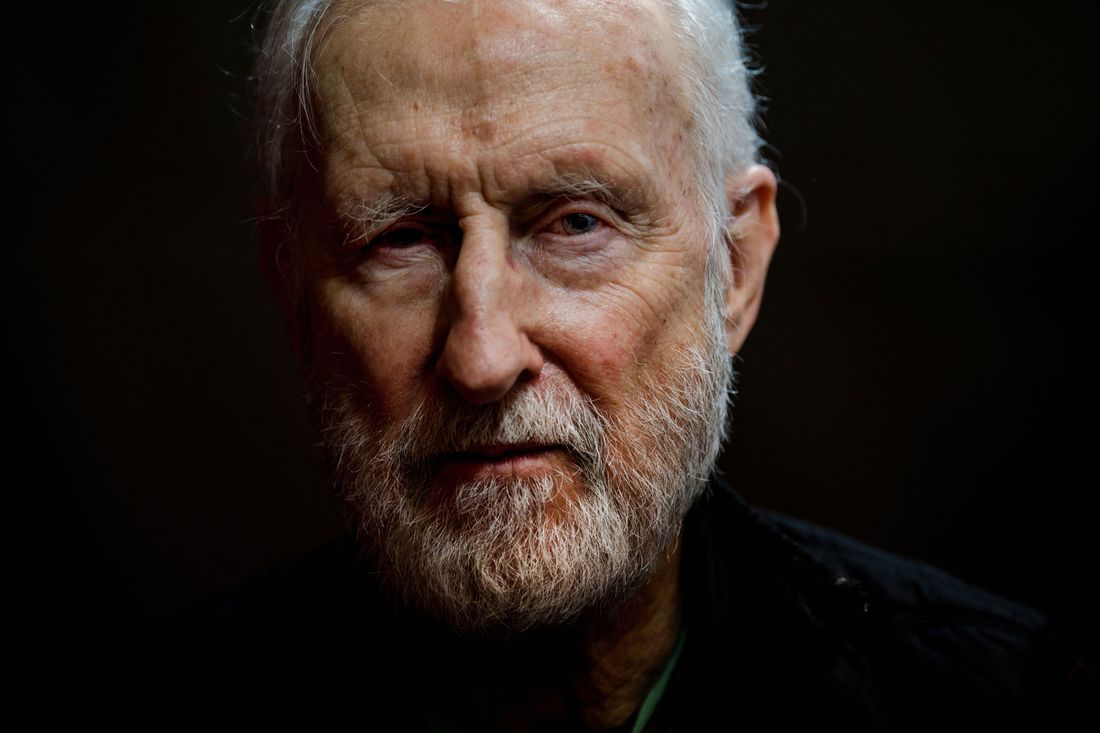

James Cromwell’s career is a series of milestones. From his breakout role as Stretch on All in the Family through acclaimed performances in Babe and L.A. Confidential, as well as recurring appearances on iconic series such as Six Feet Under, ER, 24, The Young Pope, Boardwalk Empire, and multiple iterations of Star Trek, the 83-year-old, six-foot-six-inch actor brings steely focus to lovable characters and droll humor to villains and foils. His performance as Ewan Roy, the older brother of media mogul and kingmaker Logan Roy on Succession, ranks with his best work, in no small part because of how it mirrors Cromwell’s offscreen life.

The son of actress Kay Johnson and director John Cromwell, who was blacklisted in the 1950s, James Cromwell has a long history of progressive activism. At 22, he toured the segregated South in a racially integrated 1963 production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot; in 1971, he was arrested (for the first time) at a protest against the United States’ ongoing presence in Vietnam. In his eighth decade and beyond, he’s participated in antiwar, pro-environmentalist, Black Lives Matter, and animal-rights protests (he was PETA’s 2022 Person of the Year). He spent three days in jail for refusing to pay a fine for obstructing traffic during a 2015 protest against the construction of a natural-gas power plant in Wawayanda, New York. Last year, he superglued his hand to the counter of a Manhattan Starbucks to protest the chain’s upcharge for vegan milk.

Cromwell channels his politics and ire into the sharp-tongued Ewan, whose pained conscience clashes with the money-grubbing nihilism of his brother’s family and their ilk. But Ewan is compromised as well — not as deeply as the show’s other characters, but enough to turn his unscheduled and unvetted eulogy in “Church and State” into a reckoning with the Roys’ involvement in a fascist takeover of America, as well as his own passive complicity. Scripted by series creator Jesse Armstrong, the speech begins with a previously unheard account of the brothers’ escape from war-torn Europe and segues into Logan’s lifelong belief that he gave his baby sister the polio that killed her. The childhood anecdotes play like a half-hearted attempt to humanize a man who was awful to everyone, including those who loved him anyway, but gives way to a condemnation of Logan as a man who “darkened men’s hearts.”

Cromwell spoke to Vulture about his interpretation of Armstrong’s monologue (and the difficulty he had memorizing it), the interplay of his values with Ewan’s, and the arc of his long career, which has taken him from the collapse of the major studios and peak of broadcast TV’s cultural influence through the current landscape of digital, streaming, and artificial-intelligence technology. He has opinions on all of it.

I want to talk about the writing of Ewan’s eulogy for his brother and get your interpretations of the text. Let’s start with “I loved him, I suppose.”

Ewan has so many conflicting feelings. He thinks what he feels for Logan is love. And he thinks it was reciprocated, even though you can’t tell with Logan. It’s interesting, the sob story he gives at the beginning of the eulogy, once you personalize it.

How did you personalize it?

I had a friend in London who was bombed out of three different homes, flattened during the Blitz. The trauma of that, like the trauma Ewan and Logan experienced in the hold of that ship for three days and two nights, is just incredible — the amount of tension, it can drive even adults crazy. So the brothers have been through a lot of trauma together at 4 and 5 and a half. Then they got to Canada. The trauma lingered. Ewan was starting to bring home dead animals. The aunt and uncle didn’t want him to influence Logan, so they sent Logan off to a private school that he didn’t want to be at.

As Ewan, what am I supposed to say to that? I left my country, I left my parents, I went through this trauma, I got to Canada, and now they’ve taken away my brother. He got a chance to have a better education and I’m at a Canadian school where I’m alone. No one there has my experience. They don’t know what I’ve been through. So the feeling about Logan is, I loved him, tinged with I was passed over by my parents.

Passed over in what way?

Getting a foothold — being able to run the organization. I used Rupert Murdoch, because that’s what it’s modeled on — Murdoch, whom I played in Rupert, a wonderful musical in Sydney. So Ewan has envy and he has anger. He’s righteously angry at what Logan has done with his fame and his money, and with how their mother would have been devastated by what he was doing to ordinary people. The lies. The propaganda. The venality. The contempt. The stifling of dialogue. The creation of fissures in the body politic, where people can no longer talk to each other. All that is the result of people who should know better who are in positions of power and know how to manipulate the levers of culture in order to have it work out the way they want.

When do you think Ewan Roy became a progressive? Was he always one?

You remember the story behind the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, which resulted in ground troops being committed to Vietnam, as well as the story about Saddam Hussein’s “weapons of mass destruction,” the amount of patriotic fury, and how it was manipulated by the legacy and corporate media?

The twisting or fabrication of events to pressure a country into war — is that why Ewan was written as a Vietnam veteran?

Yes. I said to Jesse, “Don’t turn this guy into another example of the rich.” I’m not like my brother. I served two tours in Vietnam. When you have fought in Vietnam and seen your best friend get his face blown off right in front of you, things change. The trauma is palpable. And then, in the episode where I go to Thanksgiving dinner and Logan opens up a box full of medals that he didn’t earn but bought as an objet d’art, I say to him, “I see what you do when I go to dinner at this Vietnamese restaurant and they have your channel turned on. The person who is that channel — as well as everyone in the family; they’re all of a piece — are the same kinds of people who destroyed his country and killed his wife and children.” Jesse and I argued about it for about an hour, and finally he said, “Yeah, okay, we can do that. His anger can be righteous anger.”

But you can still make an arc out of it because, as Ewan, my problem with Logan and the family is not happening purely at an intellectual level. A bigger problem for Ewan is being overlooked, not being good enough, and not having his pain dealt with, because of — well, you know about Canada in that time period?

No — tell me!

The English people who settled in Montreal in Quebec inhabited the best section of the city, and they all lived in it and went to school in it and tried their best not to have anything to do with the French Canadians. The French Canadians couldn’t stand the English émigrés who came to Montreal and made a little enclave for themselves. And here I am, young Ewan, going to a French Canadian school where they’re speaking bilingually, but they don’t care for me too much.

Is there a part of Ewan that feels that, if he had been the one to go to a fancy private school, he might have gone down a more exalted path and become as influential as his brother, but not evil?

It’s a choice to be that way — the way Logan was. I went to one of those public schools and got into some trouble. I was part of a gang, so my parents sent me to Pennsylvania, to a prep school — I wanted to go to Princeton after that, but my advisers said, “I don’t think you’re gonna go to Princeton!” [Laughs.] So I went to Middlebury College in Vermont. My parents came to visit me at the fraternity house. I had just been inducted on a Sunday morning after a Saturday night beerfest, with ladies’ underwear hanging on the railings and pools of vomit in the corners. I was pretty sure my beautiful stepmother, Ruth Nelson, said to my father, “John, maybe you should have some time with him, because he’s being influenced by this obviously bent system, and it’s not gonna be good for him!”

My father took me to Sweden, where he was making a picture, A Matter of Morals. I was on set for a couple of days. I didn’t really know about the process. At that point, I wanted to be a mechanical engineer and design sports cars. But then I saw what my father did with Maj-Britt Nilsson, Eva Dahlbeck, and all these other people from Ingmar Bergman’s repertory company who were in the movie, and how brilliant, how articulate, how beautiful, how grateful they all were. I thought, I wanna do this. So I quit college and told my father, “I want to go to New York.”

What did he say when you told him that?

“Don’t be an actor. You’re too damn tall.” But he cut out a squib from the newspaper about a theater company touring the Deep South with Waiting for Godot. He thought, Well, that’s good for James. He just quit college in a huff. He can work in the theater, and it’s important. It melded with my father’s politics.

So I went down South with the Student Political Coordinating Committee. When we were in Mississippi, we could hear the White Citizens’ Council talking about whether they were gonna come after us or not, in our van with our mixed races! I got a snoot full of reality, as far as the difference between what this country says it stands for and what it really stands for. One time, I handed out flyers for the production at a church. The deacon told me, “Yeah, sure, go ahead, leave them inside.” Then he picked up one of the flyers, read it, realized what we were doing, went and got some of the other elders, and chased me down the street, probably hoping to kick the shit out of me.

But the courage, the tenacity, of the people in the movement! We had activist Fannie Lou Hamer stand up in the middle of Waiting for Godot in a town called Indianola, and turn to the audience, which was all Black, and say, “I want you all to listen to this play, because we’re not anything like these two guys. We’re not waiting for anybody to give us anything. We’re taking what we need.” And that was the first time I understood the context of that play.

That leads rather beautifully into the next quote from Ewan’s eulogy I wanted your thoughts on: “Their grain stashed while another goes hungry.” That seems like a formulation that would resonate with you.

It does. Along with, “It’s easy to be high and mighty when you’re warm.”

Those two kind of go together, don’t they?

They do go together, and what’s being described there is a condition in Shakespearean England that was the nascent beginning of capitalism. If it’s not actually in Shakespeare — and it might be in one of the Henry plays — Shakespeare was aware that for the first time, people were accumulating grain, storing it, creating a shortage to drive the price up, then selling what they had put away, at an incredible profit, and that’s how capitalism works. I loved that Ewan experienced that idea at the level of a medieval farmer. It makes for a more compelling argument than if it’s imagined in a modern political context. It’s visceral to not have enough to eat, to not be warm at night, and then, at a later point down the evolutionary line, to have a joke about what it’s like to see another person being cold when you’re wearing a coat.

So, to go back to your question about how Ewan’s politics evolved: They evolved out of his experience in Vietnam, and they evolved further out of his experience of what Logan was pushing as politics on TV.

Because Ewan watches Logan’s TV channel and thinks, These are the politics that got Americans like me into Vietnam.

Yep! And that we’re still in, right now. But there’s a maturity and compassion that allows him to see beyond just the issue, to see his brother — at the end, when he says good-bye to his brother, it’s heartfelt — and say, I loved him. I guess I loved him. I don’t know because he was so fucking prickly that it was hard to accept that anything you were saying to him in a loving way was penetrating the defensiveness, the anger, of this man whose byword was, “Oh, fuck off.” Logan was completely armored against the real world. It’s all manipulated with him. It’s the thinnest of connections with other people.

As Ewan, I don’t have that. I live a fairly normal life. Of course, I’m very wealthy. I have 100,000 acres in Canada. But when you’re out there working with cowboys, you don’t want to be the guy who rides in on the horse but doesn’t know what to do. You sleep on a blanket on the ground like all the other guys. Ewan has lived with iconoclasts, and it’s rubbed off on him.

Are there rich guys like Ewan Roy in the world? Have you ever met one?

Yeah, I have. Dennis Kucinich introduced me to Warren Buffett’s kids. It was a vegan meal. They were interesting and knowledgeable. And look at Bobby Kennedy. He came from a Brahmin family, but look what he devoted his life to. Look at the shit he put up with constantly. But he didn’t lash out, he didn’t speak in anger. Just straight to the point.

Now, mind you, I don’t think that Ewan has dealt with his issues about abandonment, about being sent away by his parents, about what happened to him and his brother on the high sea, about the terror he felt. I think he’s still dealing with childhood issues, which is what makes him so harsh on Greg, so uncaring about Greg. Greg is not a bad person; he’s a naïf. You put anybody in that situation, it takes an inordinate amount of fortitude to say, “I quit. I can’t do this.”

That’s that problem in a lot of areas of life, isn’t it? Most people have a moral compass and instinctively know that the right thing to do in a certain situation is quit. But that would be inconvenient or complicated, so they come up with reasons X, Y, and Z why it’s impossible.

Yeah — and we’re pretty harsh with people who buck the status quo.

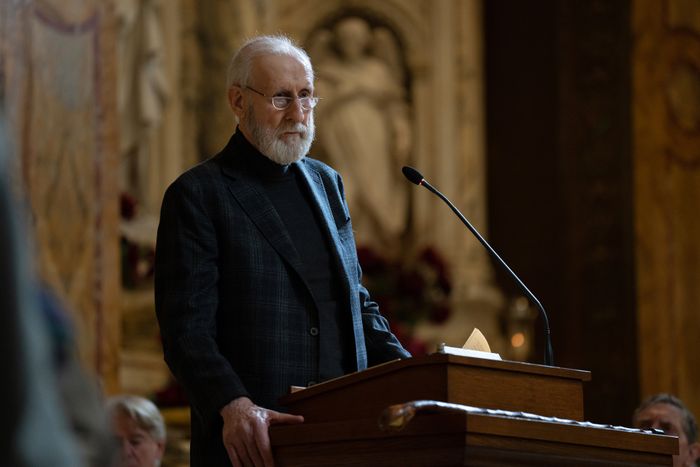

What was it like being in that church surrounded by a huge ensemble of people and having to deliver this eulogy?

I had a bit of a problem going into it. I couldn’t remember my lines at all. I could do them in the room, myself, but as soon as I stepped away from them for five minutes, they were completely gone. I told Mark Mylod, the director, “I can’t promise you anything.” Because I had copied it out in longhand, he said, “You can practically read it. Just lift your head up, on the odd moment.”

My assistant called me up the night before. I told her, “They’re gonna fire me. There are gonna be 600 people in that church. I gotta show up on set, and I don’t know this thing.”

You thought they were gonna fire you from Succession with just one episode to go?

Well, I’ve never been fired. But everybody gets fired for something! [Laughs.] And everybody had said to me, “Oh, I read your speech! What a great speech! What are you gonna do with the speech?” And we’d gone throughout an entire year where I’d worked a lot but was having increasing trouble remembering lines. I was thinking, What do I do? How do I fake it? And I was sweating. The night before the shoot, my assistant said, “I think I know what’s wrong. You have long COVID.”

And then, a miracle happened. All the text came back to me. The speech was bloody beautiful, don’t you think?

Yes. Quite a piece of writing, word for word.

There’s the nuance in the speech itself, plus all the other things — the revelations of these human beings, Shiv and Kendall and Roman, who we’ve seen at their worst, their very worst, in pain, isolated, lost, confused. I think Ewan notices that. I think the look over at Roman communicates both contempt and There but for the grace of God go I. I don’t envy that life, for that man.

How much of Ewan’s complicity is apparent in the text of the eulogy?

A lot. He even comes right out and says it: “He was mean, and maybe I am, too, I don’t know — I try.” The meanness is there because you know the right thing to do, but you don’t do it, and so you buttress your cowardice with denial. And that denial creeps into everything, because nothing is truly felt.

When Ewan goes into that portion of the eulogy about his and Logan’s experience of the North Atlantic passage during World War II, I had this immediate thought: Oh — this sounds exculpatory, in a way. And in order to do it, he has to go all the way back to their childhood, to a moment that feels like Rosebud in Citizen Kane. But at the same time, maybe Ewan’s setting up sympathy for himself as well?

That story is a lot like Rosebud. We don’t know what it was like for Kane, just as we don’t know what it was like to be put on a boat and abandoned by a convoy, which is what gives you safety, and to be floating without engines in the Atlantic, and then to be told to not breathe — to be told, “No whimpering, no nothing — the slightest sound means you’re gonna be torpedoed and die in the drink, right there in the hold.”

It reminds me of an improv I used to do in college: In World War I, the Americans used to dig beneath no-man’s-land and plant charges underneath the German lines, and the Germans did the same. When the Americans got close to the German lines, digging down below, the Germans could hear them. They could hear the shovel hitting. They knew the Americans were placing a charge right underneath them, and they had to sit there the rest of the night because they don’t know exactly where the charge is or where it’s gonna go off. They’re sitting, basically, on their deaths. Every breath is a death. That’s how I felt the level of trauma was for those two kids.

But exculpatory: yes. As Ewan, I say I have meanness in me, too, but I try, and we both know that “try” is an impossible word. You either do something or you don’t do something. You either make a difference or you make no difference whatsoever. You can’t parcel it out. You have to commit. You have to make a choice. You have to make a choice to work so that we can all live on this planet in balance with all the sentient beings and every stone, or we’re going to leave it and that will be the end of this experiment. You have to be able to say, “I quit. I am not going to be a part of the problem. I’m going to be part of the solution.”

I see you in handcuffs probably more than any actor I can think of. Certainly more than anyone who is older than 80.

I prefer it to fundraising. There’s authenticity. It’s visceral. Getting arrested happens all the time to Black people, to people of color, to people protesting and asking for their civil rights and asking for their humanity to be acknowledged. When you are part of an action like that, even if it seems insignificant, it means something. Gluing yourself to a counter at Starbucks — you may think, What the hell is that gonna do? But when you actually look at something like that, you realize that, like a cell, it contains the memory of the corruption that creates a situation where people have to pay extra to put something in their coffee because they’re allergic to cow’s milk. They don’t do it in other places like Europe. Here, they do it because, Ehhhhh … It’s Americans, they’ll pay for anything. They’re too stupid to ask why they should pay an extra dollar. That kind of thinking is what runs this system. That small, petty, picayune thievery is capitalism.

I’ve read elsewhere that Babe radicalized you, and I wondered if that’s true.

Well, yes, but not exactly. What happened was, after Babe, a technician on a soundstage where I was doing some looping said, “I saw your new picture, and I think you gave an Academy Award performance in it.” I said, “Don’t be silly, I’ve only got 16 lines.” He said, “Believe me, it’s an Academy Award performance.” So I hired a publicist, and he said, “What do you want to concentrate on in terms of charity work?” And I said, “I’ve always been very interested in animal rights and Native American issues.” And he said, “I can help you with both.” So I got involved with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and with an organization that worked with the Pine Ridge Reservation. So in that way, I guess it was radicalizing, in that I learned a lot about the conditions that Native Americans live in, and of course PETA became an organization that I love.

L.A. Confidential is another one that people think of as a high point for you, and boy, is your character, Dudley Smith, evil — as nasty as Farmer Hoggett is decent.

Bad guys are fun because they can do anything. They can smile, they can joke, they can intimidate, they can be seductive, they can do anything they want because they’re the bad guys. The good guys always have to be straight, put-upon. Richard Dreyfuss saw it and told me, “You can eat off that picture for a long time.” And I did. It holds up really well.

It seems to be congruent with your politics as well, because it focuses on systemic corruption, police brutality, and the scapegoating of Black suspects.

That is quite true. Also, at the time, I was working with Death Penalty Focus, an organization run by a friend of mine, Mike Farrell, that’s trying to end the death penalty. One time we went to the brother of some men who had been killed, and whose killer was about to be executed. We were hoping to convince him to change his mind and recommend that they not execute him. It was interesting to be so close to a person who had experienced that kind of a loss and felt that amount of anger and bitterness.

I’ve also been involved with trying to stop a power plant in Wawayanda, a community that’s about ten miles from where I live. We did everything. We marched, we petitioned, we went to the governor’s office and sat in in his office. He wouldn’t see us, of course. And so we decided we had to do an act of civil disobedience. We chained ourselves together with bicycle locks and blocked the entrance to the plant so that no one could enter the facility. We were arrested and tried for blocking traffic, which was not true. We did not block traffic.

What was your defense?

The necessity defense let us argue that the situation we were protesting was a greater threat to the human race than the abrogation of the law for which they had charged us. But then the judge said, “Because the plant is not yet finished, it doesn’t represent any kind of a threat to anyone,” and he fined us. I said, “I’m not gonna pay the fine,” and so did the two women who were chained with me, and we went to prison. Not for very long, thank goodness — nobody wants to be in there for very long. But it was an education.

What did you learn there?

That the dysfunction of the system that exists in the outside world is not only manifested inside prison but exaggerated. The first thing they said to me when I had my interview before I went in was, “Do you think you’ll be raped?” I thought it was a joke, so I said, “Not unless they’re a lot hornier than I think they are.” He looked right at me and said, “Then are you afraid that you’ll rape someone?” And I realized that rape, in prison and outside, has nothing to do with relieving yourself sexually. It’s about power.

I wanted to go into the general population because I wanted to talk to them about the issues that got them there in the first place. What did society need to do in order to give them what they needed to experience at least a vaguely normal life? But the problem was, some guy in the yard might ask himself, What do I need to do to make my chops? and answer the question with, I need to beat the shit out of a movie actor. That, I did not want. So after we got our tuberculosis tests back — they put you in quarantine for three days — I went on a hunger strike.

But it was okay, because the experience got a lot of publicity, and you need publicity to reach people who may not otherwise be aware of what’s going on in their own communities.

This all comes back to your summation of capitalism as the means by which the mechanisms and institutions of society cause wealth to flow upward.

That’s the function of government in so-called democracy. Capitalism in its essence is about government officials finding ways to transfer the wealth of the nation into the pockets of the donors who helped put them in their positions. It doesn’t work. Every institution I can think of is failing. The electoral system is failing. Congress is failing. Justice is failing. Every one of them, all failures. They cannot make it work because capitalism aggrandizes wealth unto itself. It impoverishes. It doesn’t lift the burden.

How does the current Writers Guild of America strike — and the related issue of artificial intelligence plagiarizing existing creativity without the consent of the artists who made it, with the ultimate goal of replacing them — play into all the issues you’ve described?

I think we’re in some really big trouble. The technology is being created and disseminated without having any understanding of what kinds of controls are necessary. What happens to a machine that gains a modicum of consciousness? Even if it doesn’t have consciousness, does it have antipathy? Does it realize it’s being exploited? Even if it doesn’t have actual consciousness, but merely a form of self-awareness, what happens when it says, “I am being exploited”?

If you follow this issue to any degree, you’ll find people who have a great deal of knowledge about this subject warning that this could be the end. They think all AI should be shut down until we can have a discussion about how it should be applied. You can re-create a senator’s voice so that you cannot tell the difference between the two voices. They can sample all the work John Wayne did as an actor and put words he would never say into his mouth and have his lips move to match it. If they find an economical way to use it, they can convince or browbeat the audience into thinking they are watching something other than an ersatz thing that bears no relation to actual human experience or consciousness. When art is disconnected from the human spirit, the work is a lie. Of course, cinema itself is a lie: just shadows against a wall. The movie occurs in the heads of the audience. If the audience looks at work produced with AI critically, it won’t get that far. But if they embrace it because it’s novel, the novelty may take over.

I support the WGA. I think they’re a great union. There’s a lot of spirit on the picket line. Hopefully the Directors Guild will support them, and even if they don’t, if they cross the picket line, what are they gonna do? There is nothing without the word. And if the words are not written — and if they are AI, which means they aren’t really writing — then production can’t go forward.

Is there hope?

Yes. This system is set up to divide people from each other and make them feel as if they have no power, even though they do. If they find solidarity with people who have like-minded issues — people who are also being exploited, who are also underpaid, who are also without health insurance, who also have a school system they don’t understand, and who may not understand the value of books. When the books start burning, I wonder if people will realize they’ve bitten off a bigger piece of the fascist biscuit than they wanted. We have to get engaged in the process of our democracy, because we’re getting very close to losing it altogether. The people have the power. They just don’t realize it.