I got into this business to write great songs and have fun. I was a quick learner. I read every music magazine I could get my hands on and at 12, after digesting many issues of Creem, I decided to base my personality on Lester Bangs, the rock critic raconteur; his abiding belief in the transformative power of a great rock song matched mine. (I also obsessed over his running arguments with Lou Reed – they confounded me, but I loved it.) Artists and their songs shaped my life, my beliefs, my self-conception as a musician – Patti Smith’s growling Pissing in the River, Heart’s Barracuda, the Runaways’ Dead End Justice, which I still know every word of. But what no magazine or album could teach me or prepare me for was how exceptional you have to be, as a woman and an artist, to keep your head above water in the music business.

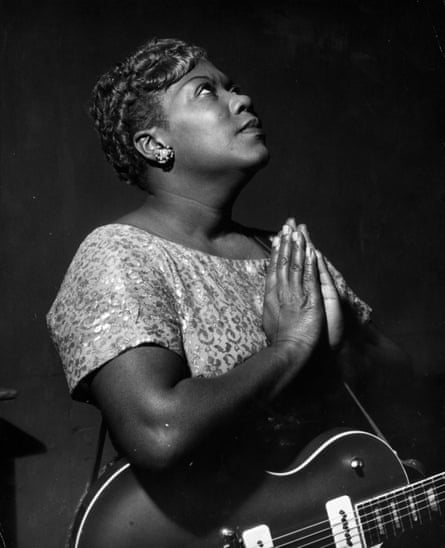

The magnificent Chuck D rapped: “Elvis is a hero to most, but he doesn’t mean shit to me.” I concur. Big Mama Thornton first sang Hound Dog, written for her (and possibly with her) in 1952, which later put the King on the radio. Sister Rosetta Tharpe covered it, too, hers being the fiercest version. Her song Strange Things Happen Every Day was recorded in 1944. It was these songs, and her evangelical guitar playing, that changed music for ever and created what we now call rock’n’roll.

When the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame started in 1983, you would have thought they might want to begin with Sister Rosetta, with those first chords that chimed the songbook we were now all singing from. The initial inductees were Chuck Berry, James Brown, Ray Charles, Little Richard, Sam Cooke, Fats Domino, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley; not a woman in sight. Sister Rosetta didn’t get in until the Rock Hall was publicly shamed into adding her in 2018. (She was on a US postal stamp two decades before the Rock Hall embraced her.) Big Mama Thornton, whose recording of Ball’n’Chain also shaped this new form of music? Still not in. Today, just 8.48% of the inductees are women.

The nominations for this year’s class, announced last month, offered the annual reminder of just how extraordinary a woman must be to make it into the ol’ boys club. (Artists become eligible 25 years after releasing their first record.) More women were nominated in one year than at any time in its 40-year history. There were the iconoclasts: Kate Bush, Cyndi Lauper, Missy Elliott; two women in era-defining bands: Meg White of the White Stripes and Gillian Gilbert of New Order; and a woman who subverted the boys club: Sheryl Crow.

Yet this year’s list featured several legendary women who have had to cool their jets waiting to be noticed. This was the fourth nomination for Bush, a visionary, the first female artist to hit No 1 in the UK chart with a song she wrote (1979’s Wuthering Heights), at 19. She became eligible in 2004. That year, Prince was inducted – deservedly, in his first year of eligibility – along with Jackson Browne, ZZ Top, Traffic, Bob Seger, the Dells and George Harrison. The Rock Hall’s co-founder and then-chairman Jann Wenner (also the co-founder of Rolling Stone) was inducted himself. But Bush didn’t make it on the ballot until 2018 – and still she is not in.

Never mind that she was the first woman in pop history to have written every track on a million-selling debut. A pioneer of synthesisers and music videos, she was discovered last year by a new generation of fans when Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God) featured in the Netflix hit Stranger Things. She is still making albums. And yet there is no guarantee of her being a shoo-in this year. It took the Rock Hall 30-plus years to induct Nina Simone and Carole King. Linda Ronstadt released her debut in 1969 and became the first woman to headline stadiums, yet she was inducted alongside Nirvana in 2014. Most egregiously, Tina Turner was inducted as a solo artist three decades after making the grade alongside her abuser, Ike.

Why are women so marginalised by the Rock Hall? Of the 31 people on the nominating board, just nine are women. According to the music historian Evelyn McDonnell, the Rock Hall voters, among them musicians and industry elites, are 90% male.

You can write the Rock Hall off as a “boomer tomb” and argue that it is building a totem to its own irrelevance. Why should we care who is in and who is not? But as scornful as its inductions have been, the Rock Hall is a bulwark against erasure, which every female artist faces whether they long for the honour or want to spit on it. It is still game recognising game, history made and marked.

The Rock Hall is a king-making force in the global music industry. (In the US, it is broadcast on HBO.) Induction affects artists’ ticket prices, their performance guarantees, the quality of their reissue campaigns (if they get reissued at all). These opportunities are life-changing – the difference between touring secondary-market casinos opening for a second-rate comedian, or headlining respected festivals. The Rock Hall has covered itself in a sheen of gravitas and longevity that the Grammys do not have. Particularly for veteran female artists, induction confers a status that directly affects the living they are able to make. It is one of the only ways, and certainly the most visible, for these women to have their legacy and impact honoured with immediate material effect. “These ain’t songs, these is hymns,” to quote Jay-Z.

The bar is demonstrably lower for men to hop over (or slither under). The Rock Hall recognised Pearl Jam about four seconds after they became eligible – and yet Chaka Khan, eligible since 2003, languishes with seven nominations. All is not lost, though – the Rock Hall is doing a special programme for Women’s History Month on her stagewear ...

What makes Khan’s always-a-bridesmaid status especially tragic is that she was, is and always will be a primogenitor. A singular figure, she has been the Queen of Funk since she was barely out of her teens. As Rickie Lee Jones said: “There was Aretha and then there was Chaka. You heard them sing and knew no one has ever done that before.”

Yet Khan changed music; when she was on stage in her feathered kit, taking Tell Me Something Good to all the places it goes, she opened up a libidinal new world. Sensuality, Blackness: she was so very free. It was godlike. And nothing was ever the same.

But for all her exceptional talent and accomplishments – and if there is one thing women in music must be, it is endlessly exceptional – Khan has not convinced the Rock Hall. Her credits, her Grammys, her longevity, her craft, her tenacity to survive being a young Black woman with a mind of her own in the 70s music business, the bridge to Close the Door – none of it merits canonisation. Or so sayeth the Rock Hall.

The Rock Hall’s canon-making doesn’t just reek of sexist gatekeeping, but also purposeful ignorance and hostility. This year, one voter told Vulture magazine that they barely knew who Bush was – in a year she had a worldwide No 1 single 38 years after she first released it. Meg White’s potential induction as one half of the White Stripes (in their first year of eligibility) has sparked openly contemptuous discourse online; you sense that if voters could get Jack White in without her, they would do it today. And still: she would be only the third female drummer in there, following the Go-Go’s Gina Shock and Mo Tucker of the Velvet Underground. Where is Sheila E – eligible since 2001?

It doesn’t look good for Black artists, either – the Beastie Boys were inducted in 2012 ahead of most of the Black hip-hop artists they learned to rhyme from. A Tribe Called Quest, eligible since 2010 and whose music forged a new frontier for hip-hop, were nominated last year and again this year, a roll of the dice against the white rockers they are forced to compete with on the ballots.

If so few women are being inducted into the Rock Hall, then the nominating committee is broken. If so few Black artists, so few women of colour, are being inducted, then the voting process needs to be overhauled. Music is a lifeforce that is constantly evolving – and they can’t keep up. Shame on HBO for propping up this farce.

If the Rock Hall is not willing to look at the ways it is replicating the violence of structural racism and sexism that artists face in the music industry, if it cannot properly honour what visionary women artists have created, innovated, revolutionised and contributed to popular music – well, then let it go to hell in a handbag.

Courtney Love is a singer, musician and actor