I have always admired John le Carré. Not always without envy – so many bestsellers! – but in wonderment at the fact that the work of an artist of such high literary accomplishment should have achieved such wide appeal among readers. That le Carré, otherwise David Cornwell, has chosen to set his novels almost exclusively in the world of espionage has allowed certain critics to dismiss him as essentially unserious, a mere entertainer. But with at least two of his books, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) and A Perfect Spy (1986), he has written masterpieces that will endure.

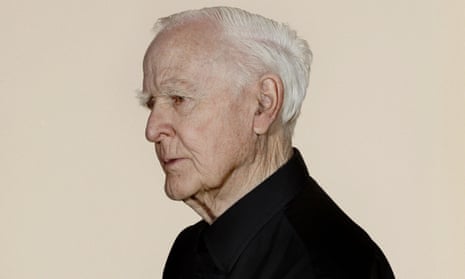

Which other writer could have produced novels of such consistent quality over a career spanning almost 60 years, since Call for the Dead in 1961, to his latest, Agent Running in the Field, which he is about to publish at the age of 87. And while he has hinted that this is to be his final book, I am prepared to bet that he is not done yet. He is just as intellectually vigorous and as politically aware as he has been at any time throughout his long life.

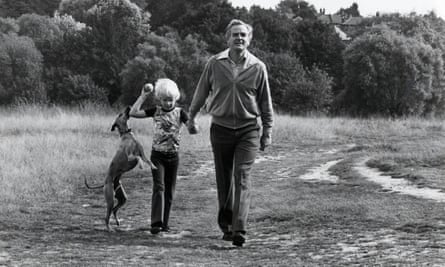

In the new book there is a plotline that is predicated on covert collusion between Trump’s US and the British security services with the aim of undermining the democratic institutions of the European Union. “It’s horribly plausible,” he says, with some relish when we meet in his Hampstead home. His relish is for the fictional conceit, not its horrible plausibility, and at once his conman father pops up with his large-browed head and his all too plausible grin. Ronald “Ronnie” Cornwell was a confidence trickster of genius, of whom his son is still in awe, and to whose exploits and influence he returns again and again, to the point of bemused obsession. “I’ve had the good fortune in life,” says le Carré, “to be born with a subject” – no, not the cold war, which many foolishly imagined was his only topic – “the extraordinary, the insatiable criminality of my father and the people he had around him. I Googled him the other day and under ‘profession’ it said: ‘Associate of the Kray brothers’.” This gives us both a laugh, though a queasy one.

“A ceaseless procession of fascinating people” wound its felonious way through his childhood. In his earliest days he was “relieved of any real concept of truth. Truth was what you got away with.” All too familiar to him, then, are the frauds who have swaggered their way into the spotlight in today’s political pantomime.

It seems to le Carré now entirely natural that escape from the toxic background of his childhood should have been entry into “severe institutions”. He was sent to his first boarding school at the age of five – “and I did five years straight of stir”. He went on to Sherborne school in Dorset, which he hated – in later years the head of the Secret Intelligence Service, David Spedding, told him that what he most admired him for was the fact that “you ran away from Sherborne while I stayed the course”. Spedding’s rueful warmth is in marked contrast to the recent attack on le Carré by another former head of MI6, Richard Dearlove, who last month at a literary festival in Cliveden – of all places – said the writer was “obsessed” with his brief time as a spy, which he had used as a basis for novels that reveal him to be “so corrosive in his view of MI6 that most SIS officers are pretty angry with him”.

For all his sufferings under the educational system of the day, boarding school was for le Carré “one route in the search for some sort of clarity about behaviour”. Then came “the glide into the secret world”: at Oxford he was approached by the security services and did some spying, and informing, on his fellow students of the left-leaning sort, something of which he does not repent. John le Carré, or better say David Cornwell, is at heart an old-fashioned, romantic English patriot. For all that, he is not deluded about the mores of the “secret world”. The security services fixed on their candidates “for being on the one hand larcenous” – a favourite word – “and on the other hand, however you call it, loyal”. This dichotomy raised “huge, many-faceted questions”, for instance what distinguishes patriotism, good, from nationalism, bad. That particular question “kicked around in me ever after. It remains unresolved.”

I mention a passage in Agent Running in the Field in which the protagonist Nat, short for Anatoly, a middle-aged, Russo-English secret agent, is watching on screen a surveillance operation being carried out in the streets of London, and is suddenly, and surprisingly, seized with admiration for his country and its people: “multi-ethnic kids playing improvised netball, girls in summer dresses basking in rays of the endless sun, old folk sauntering arm-in-arm ... ” The irony, as Nat cannot but be aware, is that about 100 of these innocent-seeming folk, including the friendly police officer who “strolls comfortably among them”, are in fact British agents busy about their clandestine work. Freedom is fragile, and must be protected by all available means, even the tainted ones.

Le Carré speaks of his grandchildren who are “all appalled by Brexit and the concept that freedom of movement is being taken from them, and so on. I say: ‘Look, actually, you have lived in many foreign cities, and you know that you will never get better conversation, a greater sophistication, more ease of social contact, than in London or in Britain altogether.’”

I tell him that I lived in London for a year at the end of the 1960s and, coming from an Ireland that in those days was still firmly locked in the stranglehold of the Catholic church, I was endlessly surprised by the freedom of movement that was allowed to me, especially up and down the rungs of the infinitely graduated English class system. “Ah, yes,” he says, with a melancholy smile, “but you were not branded on the tongue.”

In Cornwall, where he and his wife, Jane, live for a good part of the year, “dealing with traders, and going to cafes and so on, I find that nobody knows, or cares, who I am”. This is, he feels, an example of “the absolute ease of association” there is in at least that part of England, where there is “a real sense of democracy”.

I agree with him, though perhaps not wholeheartedly – I am Irish, after all – on the British commitment to liberal values and the civilised life. But surely all that is now at risk, with the country so divided on Europe?

“Yes it is, because in the first place reason has no natural voice. Mob orators of the sort we have, the Boris Johnson sort, do not speak reason. When you get into that category, your task is to fire up the people with nostalgia, with anger. It’s almost unbelievable that these people of the establishment – Farage, for instance – are speaking of betrayal: ‘I’m betrayed by parliament, betrayed by government – I’m speaking to you as a betrayed person, and I’m a man of the people like you.’”

He is profoundly worried by the present state of his country. Johnson and his svengali, Dominic Cummings, are running what le Carré recognises as a highly sophisticated propaganda campaign to convince the people that they are their true champions, arrayed with them against the power of parliament and the political elite. This, he says, is a breathtaking sleight of hand that could bring about serious civil disorder. “And absolutely the most terrifying thing that could happen is that the EU should cave in on some minor point regarding the backstop, Johnson blows the dust off May’s withdrawal agreement, adds his own spin, claims a great victory, gets it through a frightened parliament, and rules for eight years.”

Yet all is not bleakness and cause for ire. “I think everything is controllable if the social contract is restored. You cannot preach a level playing field in this country as long as you have such exclusive institutions as private education, private medicine, private everything.” There is also the pervasive and pernicious influence of what have come to be called social media – though how far they are truly “social” is moot. “People are shown so many treats, and urged as to what to buy and what to wear and where to travel to, all of which pumps up a spurious notion of the perfect life.”

How to combat these dangerous fantasies? “I believe we have to do the things that other countries do pretty painlessly. We have to have a wealth tax, we have to limit hugely the amount of inherited wealth anyone can receive. And none of these things has happened.”

But who would make them happen?

“Well, we have an extraordinary situation with our Labour party, if they do get in and they can shed Corbyn – I think Corbyn would quite like to go, actually – but they have this Leninist element and they have this huge appetite to level society. I’ve always believed, though ironically it’s not the way I’ve voted, that it’s compassionate conservatism that in the end could, for example, integrate the private schooling system. If you do it from the left you will seem to be acting out of resentment; do it from the right and it looks like good social organisation.”

I tentatively suggest that by this stage we might sound like two crusty old codgers being sentimental about an imaginary golden age. He ponders this for a while, then sets off on a tangential tack. “You could say that with the demise of the working class we saw also the demise of an established social order, based on the stability of ancient class structures. And then, the working class had the experience of war, but one can count the years when one by one people with war experience disappeared from politics and were replaced, in the main, by people with no idea of human conflict.” And he adds, with straight-faced understatement: “Human conflict has a sobering effect.”

To hear Brexiters claiming that Britain won the war single-handedly is, he says, “emetic”. “The wonderful rightwing military historian Max Hastings points out that we were bad fighters, that we were extremely badly organised, and our contribution in terms of blood and wealth and material was – I can’t say trivial, but tremendously small by comparison to the sacrifices of the other major powers. Russia lost, what, 30 million men? And in treasure, heaven knows what. We didn’t win the war in that sense. We were on the winning side by the end, but we were really quite minor players.”

His attitude to Brexit is pungently expressed in the new novel. “It is my considered opinion,” one of the characters declares to Nat, “that for Britain and Europe, and for liberal democracy across the entire world as a whole, Britain’s departure from the European Union in the time of Donald Trump, and Britain’s consequent unqualified dependence on the United States in an era when the US is heading straight down the road to institutional racism and neo-fascism, is an unmitigated clusterfuck bar none.”

You can’t say plainer than that, even if you have made yourself safe by putting the speech into the mouth of one of your invented creatures. Le Carré says squarely of Agent Running in the Field that “to me it’s quite an angry book”. But certainly it is more, and happily less, than a political rant.

“I didn’t want it to be a Brexit novel. I wanted it to be readable and comic. I wanted people to get a good laugh out of it. But if one has the impertinence to propose a message, then the book’s message is that our concept of patriotism and nationalism – our concept of where to place our loyalties, collectively and individually – is now utterly mysterious. I think Brexit is totally irrational, that it’s evidence of dismal statesmanship on our part, and lousy diplomatic performances. Things that were wrong with Europe could be changed from inside Europe.” He pauses, then goes on, less in anger than in sadness. “I think my own ties to England were hugely loosened over the last few years. And it’s a kind of liberation, if a sad kind.”

It was in this spirit that he and wife, Jane, paid a visit recently to Ireland, Jane to delve again among her own roots in Ulster, and David to visit the house in West Cork where his paternal grandmother was raised. He consulted a local archivist for information on the family. “After spending silent minutes at her computer, she looked up with a charming smile and said: ‘Welcome home.’”

I suggest that Agent Running in the Field is affirmative of the small pleasures of life, which makes the book very enjoyable. Well, he is careful to remind me again, the voice that speaks in it is not that of John le Carré, and certainly not of David Cornwell, but of Nat, the narrator. “When you’re challenged about the behaviour of characters in your own novels,” he asks me, “do you feel obliged to defend their behaviour?” My answer is that I am no more responsible for them than I am responsible for the people in my dreams. This gets a nod of assent.

Besides Nat, the two other leading characters in the book, the gangly Ed and the beautiful Florence – I notice that the women in le Carré’s books become lovelier, and younger, the older the author gets – are essentially decent people. As such, surely they are something of an anomaly? In his reply he seems to agree. “If you’re putting together a secret service you’re looking for people who can charm, who can persuade, and who are not burdened with too much moral sense. People are naturally larcenous and sufficiently hypocritical to appear virtuous and loyal, so actually you are looking for people who are almost by definition capable of betraying you.” Hence by the end of the book the decent people in it have to be put away in a place of safety.

What of his own origins as a secret agent? “From the moment I went to boarding schools I was learning to be a gent” – nice little pun – “I had none of the attitudes of the ruling class to keep me going. I didn’t have a pony, that kind of thing. My dad for part of my childhood was in prison. So I arrived in the heartland of the establishment – private education – as a kind of spy, as somebody who had to put on the uniform, affect a voice and attitudes, and give myself a background I didn’t have. And so it was a forced assimilation and I became fascinated by the class I was pretending to be a member of. And it’s no surprise to me that although I loathed my public school I ended up teaching at Eton, and it’s no surprise to me now that I was so fascinated by the interior motor of British society, and that I was drawn to what I believe is the secret centre of our administration.”

Did being a spy give him a sense of belonging, of finally finding a workable identity for himself? “Looking really – in some Faustian sense, God help me – for what the world holds at its innermost point, was a way of asking, what are we? Who were we? Which is probably an extension of the question, who the hell am I? Where is virtue to be found? Where is the altar of Englishness? And I think that really was quite a severe internal journey, and a very interesting one, in retrospect: a lost boy in search of something or other.”

But when he was a member of the security services did he feel he was in touch with the real world, as distinct from the fantasised one in which the majority of us blithely live? “Please remember, I was a very junior figure in both MI5 and MI6. So much of what in my novels is assumed to be interior knowledge is really imagined stuff. But when I was allowed to attend operational meetings I heard what bigger animals than I were getting up to, and so by the time I got out of that world – with great relief – I had a really big treasure chest of imagined operations, which were based on glimpses of the reality. But I never did anything of the least value in that world.”

The aftermath of the secret life contained moments of rich comedy. Yevgeny Primakov – former head of the KGB, “who was within a hair’s breadth of getting Putin’s job” – came to Britain for an official visit, at the end of which his one request was to meet le Carré.

“And so Jane and I found ourselves in the Russian embassy surrounded by Russians, with Primakov in front of me. He was an extremely intelligent man, quite a humanist, though at the age of 18 he was already working with the NKVD, later to become the KGB. He was charming and we had a wonderful time together, but I was so in above my pay rate that it was ridiculous. He imagined somehow that the author of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was a colleague in sophistication. And that sometimes happens to me still. People insist that I know things that I have absolutely no knowledge of, and never did have.”

We speak about his later books, set among the super-rich, in nasty foreign wars, in battles with the international pharmaceutical industry. It is apparent that he is proud of this work, and of his support for the forces of decency, such as they are. This brings us back, inevitably, to the enigma that is his father. “I puzzle hugely about his motivation. You ask me what was fun for him. I think what was fun for him were the great confidence tricks he pulled off.”

Did this not make Ronnie an artist, of a kind?

“This is the thing that fascinates me, of course: am I simply the lucky version of him?”

If so, it is we, John le Carré’s readers, who are the lucky ones

John le Carré’s Agent Running in the Field is published by Viking (£20). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p on all online orders over £15.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion