Could you tell the story of the South in 10 songs about trains? We asked a fellow who studies Southern railroads for a living.

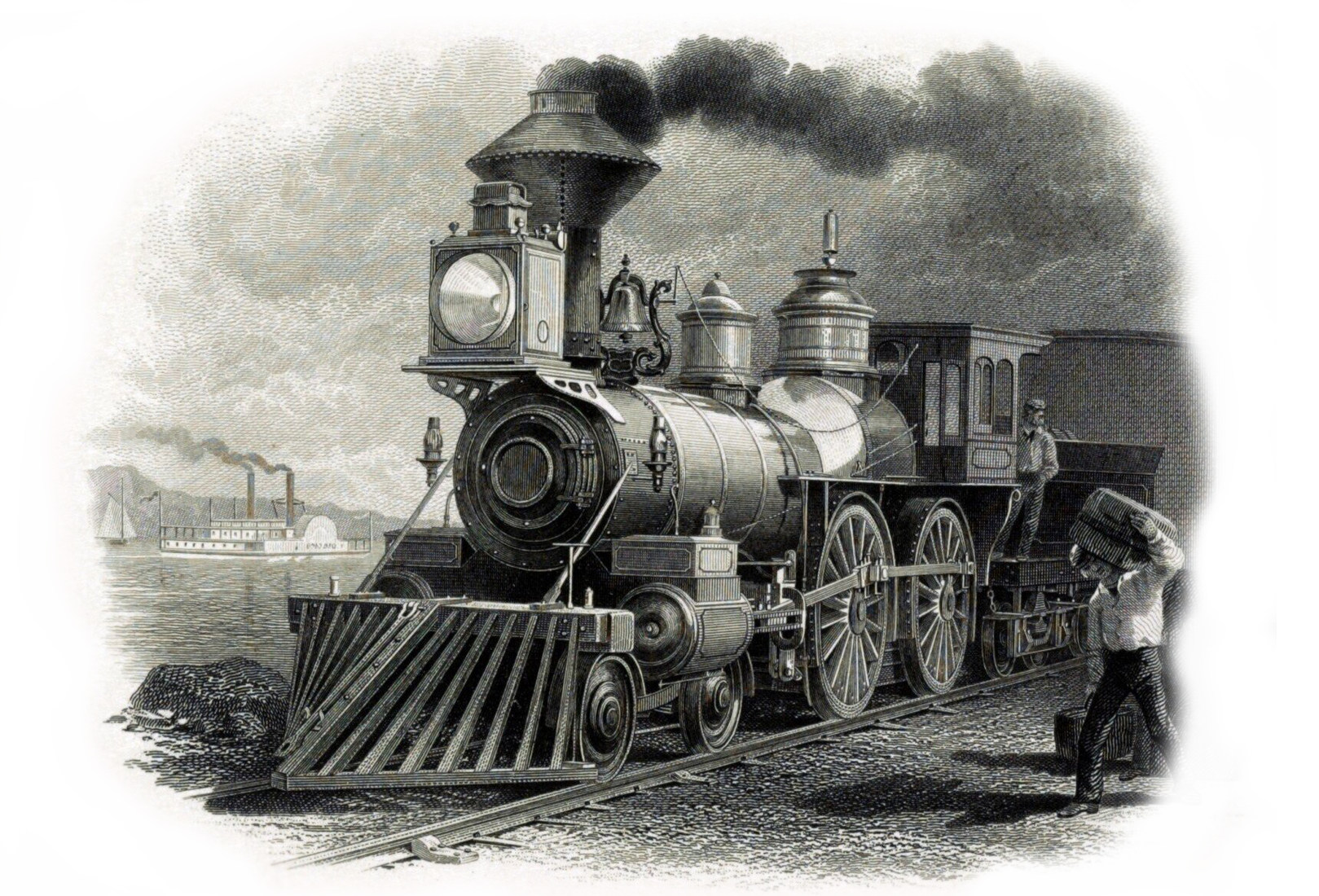

From the earliest days of railroading, American music has been unable to resist the lure of the locomotive.

While some songs use trains as passing metaphors, others feature railroads as key plot devices (e.g., the train that takes your lover away), and some go so far as to emulate the distinctive rhythms and sounds of the rail. During his explorations in the rural South in the 1910s and 20s, folklorist Howard Odum marveled at how African American musicians performed train songs that simulated the noises of speeding locomotives. The railroad has long been a powerful cultural symbol for Americans.

And most of these train songs are sung with Southern accents.

I stumbled into this connection between train songs and the South while building a playlist of train songs to accompany my research and writing for a history of Southern railroading. While this at first seemed to be a slightly obsessive diversion from the book, explaining the South’s predilection for train songs eventually became critical to the project. Southern train songs directly reflect the South’s distinctively magical and destructive history with the railroads — the very subject I was researching and writing.

White and black Southerners were entranced by the railroad and yearned for new connections, but Southern railroads were dangerous and deadly for passengers and workers. Railroads also aided the spread of disease, attracted violent robbers like Jesse James, and consolidated into monopolistic behemoths. Perhaps it is this ambivalent relationship to the railroad and the peculiarly Southern penchant for storytelling that gave Southerners so many train topics and legends to sing about?

More than just a reflection of Southern history, the evolution of the Southern train song also speaks to the various meanings American pop culture has placed on both the South and the railroad. Railroads once represented the height of modernity, but after decades of declining passenger traffic and abandonments, they now signify a bygone era. They evoke a romanticized past.

In her 2013 book Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture, historian Karen Cox argues that in reaction to the anxieties of early 20th century modernity, artists and audiences from outside the South helped perpetuate myths about the region as a slow-moving land of “moonlight and magnolias.” To go to Dixie in a song of this era was to escape to a safe, pre-industrial world, where plantations were romantic places filled with happy, singing slaves.

Those songs, of course, perpetuated pernicious myths about our region. The songs, like all “Old South” mythology, whitewashed the horrors of slavery and the Jim Crow era.

Thankfully, both Southern and national artists are now much more willing to take an unflinching look at these historic injustices, yet the trope of the South as a land behind time has persisted. As the images of the railroad and the South have merged, trains and railroad infrastructure now form part of a panoply of “down home” Southern images, existing easily in the imaginary landscape of pickup trucks, cowboy hats, old country stores, and wholesome small towns that provides the setting for much of Nashville pop-country.

But what if we imagine a new canon of Southern train songs that cut through the stereotypes of the romanticized Dixie and the sanitized music of modern country? Train songs can allow us to both recognize and move beyond these mischaracterizations of our region and grapple fully with its complicated history.

Here are ten of my favorite Southern train songs that trace the contours of the region’s railroad history. While surely not an exhaustive list, these ten Southern train songs provide a window into the shifting meanings that the South and railroads held to Americans. The list is roughly chronological, not necessarily when they were written, but in terms of the era of Southern railroad history they cover.

Virgil Caine finds himself out of a job after Stoneman’s cavalry tears up the tracks of the “Danville train,” meaning the Richmond & Danville system. Southern railroads were central to the drama of the Civil War. The Confederacy made quite effective use of its internal rail network, but these railroads became key targets of Union generals like Stoneman and Sherman, who left the twisted wreckage of rails and ties in the wake of their marches. The song unfortunately flirts with Lost Cause mythologies about the Confederacy in its focus on the white Southern experience — at the same time Virgil trudged home, African Americans across the South were celebrating emancipation and the arrival of northern troops. But Virgil’s story is still representative of the personal struggles faced by Confederate veterans. Virgil turns his back on the railroad and heads home to “work the land,” but in the decades after the war, railroads became even more essential to the South. In the 1880s, the Southern network doubled in mileage, and these new railroads became a cornerstone to the image of a New South reborn from the ashes of war.

Train-wreck ballads — songs that relate the grisly stories of railroad accidents — spread like wildfire as railroad carnage began to pile up in the South. By 1900, the rapid pace of development and shortages of capital meant that travel on Southern railroads was more dangerous than in any other part of the country, so it is no surprise that most train-wreck ballads have Southern settings. The “Wreck of the Old 97,” one of the most well known of these songs, tells the tale of the derailment of a fast mail train outside Danville, Virginia, in 1903, and it contains themes seen in many other train-wreck ballads. A failed attempt to make up lost time — perhaps a broader metaphor for the South’s struggles with industrialization — was a typical cause of these wrecks. And many songs celebrate the ultimate bravery of the conductors, who usually stay with the doomed train to save passenger lives. Steve Brady of the Old 97 was “found in the wreck with his hand on the throttle, scalded to death with the steam,” just as Casey Jones and George Alley (conductors of Engine 143) died when their engines wrecked.

John Henry’s story is without a doubt one of the most tragic in Southern railroading. As historian Scott Nelson has discovered, the real John Henry was an African American from Virginia who was swept into the convict labor system for a minor crime. Sent to work on the C&O Railroad, he then died of silicosis while digging a tunnel and he was buried in a nameless grave with dozens of others who perished while building this line. His sad fate reminds us of the horrible human cost of the South’s rapid railroad development and of the ways in which legends could grow and evolve in the highly mobile world of railroad work camps. As singers retold his story, they conjured up a version of a John Henry with unimaginable strength who emerged as the victor in a race with a machine. His legend is subject to many reinterpretations, but the Drive-By Truckers version, penned by a young Jason Isbell, is my favorite.

Railroad Bill, like John Henry, is a legendary figure whose story has gone through many transformations and edits over the years. The real Railroad Bill – a black train robber based in South Alabama in the 1890s – was about as fantastical as the Railroad Bill in song. He made a career out of robbing trains on the L&N line,1 and he used the predictable rhythms of the railroad to plan his crimes and to make his escapes. For a time, he was so successful that newspapers reported that he had taken on supernatural abilities. Some said he could shape shift into different animals, and others argued he was impervious to bullets or able to disappear on command. As the curtain of Jim Crow fell on the South in the 1890s, the actions of a black outlaw were met with an intense backlash from white southerners. Bill was gunned down in a small country store, and countless other African American men were arrested, injured, or killed by angry vigilantes. While the horror of this moment is missing from the song, it is fitting that Railroad Bill has received some posthumous redemption through music.

The image of a loved one leaving on a train is a powerful one, and as African American migration out of the South picked up during World War I, these narratives proliferated. Blues songs named after companies like the Illinois Central or L&N lament how these lines led to heartbreak for those left behind in the South. While “Yellow Dog Blues” does not exactly trace the Great Migration route from South to North, it echoes many of these songs in how it uses the railroad as an agent of romantic destruction. Poor Miss Susie Johnson’s lover has left on “a southbound rattler besides the Pullman car” and he ended up “where the Southern cross’ the yellow dog” – a junction in Moorhead, Mississippi, where the Southern Railway met the Yazoo Delta (or Yellow Dog) Railroad. W.C. Handy wrote the song in the 1910s, but to really capture the pathos of the tune, Bessie Smith’s version is essential.

By the dawn of the 20th century, nine out of every 10 Southerners lived in a county with a railroad, and businesses, homes, and towns increasingly clustered tightly along rail corridors. In this song, Elizabeth Cotton speaks to a common Southern experience in this golden age of railroading — watching a train go by. For residents of small railroad towns, a speeding train could symbolize escape, or a connection to the more glamorous, exciting outside world. For Cotton, the passing train allows her to ponder what route her train of life is on. She considers her mortality and she asks to be buried nearby so she can hear trains as they pass by. Cotton’s hometown of Carrboro, North Carolina, may no longer bear witness to a steady stream of freight trains, but the town still hugs a mostly abandoned rail corridor, and a historical marker honoring Cotton now stands watch over the tracks.

Hank Snow wants to “roll his blues away,” and his solution is to ride south on the Golden Rocket. To fight back against the withering competition from the automobile industry in the mid-20th century, railroad companies promoted glamorous streamliners with a modern look and sleek aesthetic. The struggle was ultimately futile, as the construction of interstate highways put the nail in the coffin for railroad passenger traffic, but for a brief moment these trains led to a railroad renaissance. The Golden Rocket streamliner train was planned but never actually ran, but the song still taps into the magical allure of mid-century rail travel and the romance of travel to the South. For Snow, the South is a place for escape, adventure, and romantic reunion with his lover in Tennessee. As the conductor crosses the Mason-Dixon Line, a brakeman even bursts into song. The post-WW2 South, stirring with the seeds of the Civil Rights Movement, was far from the happy, harmonious South of the song. But the song gives us a classic example of the mythic image of the South in pop culture – the region as “sunny old southland,” a place behind time and a refuge from the turmoil of the industrial North.

The City of New Orleans train traversed the Illinois Central, which connected New Orleans to Chicago. This critical corridor between North and South played host to some of the great dramas of Southern railroad history, from Civil War campaigns to Casey Jones’s infamous wreck, and the Great Migration of African Americans to northern industrial cities. In this song, Goodman takes us on a “southbound odyssey” on this route weighted with Southern history. The song can be seen as an elegy to the railroad, as it was written in the 1970s when passenger travel on railroads was spiraling downwards. The heyday of rail travel is ending, and Goodman laments the “disappearing railroad blues.” Imagery of nostalgia and faded glory pervades the song, from the car full of old men playing cards, to the decaying scenery marked with “rusted old automobiles.” The reference to “graveyards of old black men” and “sons of Pullman porters” alludes to the importance of this line to African American history as well. As Goodman’s train rolls through the Mississippi darkness, he heads south through a vanishing dreamland into the past.

Drummer Bill Berry’s driving beat gives “Driver 8” a train-like momentum — but despite the singer’s pleas, the conductor of this train is not going to stop or slow down. Michael Stipe juxtaposes the speeding Southern Crescent (a Southern Railway streamliner) with Southern gothic imagery like the preacher “selling faith on the go-tell crusade,” fields divided by stone walls, ringing bells, and power lines marked with floaters. At one point the train would be out of place in this rural idyll, but in an era of railroad declension, the train easily fades into the landscape and adds to the mystique. The line “hear the bells ring again,” places the railroad in the past and asks us to reimagine the glory years of the Southern Crescent. In the band’s early discography, R.E.M. presents the South as an enchanted space, populated with oddball characters and haunted by shadowy legends and myths. For R.E.M., this ride on the Southern Crescent and the abandoned railroad infrastructure of the South can serve as entryways into this weird South. The artwork from the band’s often-inscrutable first album “Murmur,” performs a similar feat, as it features two images from the band’s home in Athens, Georgia — a field overwhelmed by kudzu on the front and a decrepit train trestle on the back.

In this song, Gillian Welch takes the perspective of an expatriate Southerner, who is stuck in the North and missing the South. She pairs Southern imagery like strumming banjos, ripe melons, and a “river of whiskey,” with flying freight trains and the fireball (or fast train). The song’s languid tempo only helps to evoke the slower pace of the Southern countryside, and of trains creeping through the landscape in the distance. Here, the railroad again provides admission to a romanticized Southern landscape that is both out of space and out of time. The singer yearns for a return to the comfort of her Southern home, but the train is gone. The narrator laments that “they pulled up the tracks now” and they can never go back to the South they imagine. The railroad is not out of place in this imagined landscape and in her yearnings for the “Dixie Line,” we have come full circle, and the two nostalgic images of the South and the train are combined as one.

Scott Huffard is an associate professor of history at Lees-McRae College in Banner Elk, North Carolina. The University of North Carolina Press will publish his book, “Engines of Redemption: Railroads and the Reconstruction of Capitalism in the New South,” in December. You can preorder it here. His academic work focuses on 19th century American history — specifically on the expansion, consolidation, and systematization of railroads in the South in the decades after the Civil War.