Humor

Chris Rock PhD, Honorary Professor of Evo Psyc (Part 1 of 3)

Rock’s routines are funny because they invoke humans’ evolved psychology

Posted June 2, 2012

Evolutionary psychology and comedian Chris Rock have both grown increasingly prominent over the past quarter-century (Cornwell, Palmer, Guinther, & Davis, 2005; Silverman & Fisher, 2001; Webster, 2007a,b; “The Time 2008 Top 100,” 2008). This may not be mere coincidence. While evolutionary psychology (EP) has blossomed because of its unique ability to explore human nature, Rock’s stand-up routines have vaulted him into the pantheon of comedic talents because they reflect human nature.

Or so I argue in a forthcoming article in Review of General Psychology (Kuhle, 2012). Intentionally or not, Rock’s comedy is based on a sophisticated appreciation and invocation of humans’ evolved psychology. Conventional wisdom and recent EP research suggest that “something is funny because it’s true” (Clarke, 2010; Flamson & Barrett, 2008; Lynch, 2010). This perspective on humor rings especially true in Rock’s routines. The hilarity of his stand-up stems, in part, from his invocations of sex differences in the evolved psychological mechanisms underlying romantic relationships. Popular culture such as Rock’s comedy can provide a window into human nature as “the patterns of culture that we create and consume, although not adaptations in themselves, reveal human evolutionary psychology” (Buss, 2012, p. 428).

I aim to persuade you of this by reviewing EP theory and evidence that underpin 22 of Rock’s routines on romantic relationships from his five HBO comedy specials. As a warm-up for his stand-up, I begin by briefly exploring several definitions of humor and theories of its adaptive function.

What is Humor?

Much like its varieties, definitions of humor abound. Some are poetic, as when Darwin likened humor to a “tickling of the mind” (1872, p. 218). Some are bookish: among its 18 senses of the term, The Oxford English Dictionary soberly defines humor as “that quality of action, speech, or writing, which excites amusement; oddity, jocularity, facetiousness, comicality, fun,” (Humor, n.d.a). Others are, well, humorous: Urban Dictionary offers, “what makes the worst moments of our already miserable existence that more bearable” (Humor, n.d.b). Although no universally agreed upon definition of humor exists, in his impressively thorough text on the psychology of humor, Rod A. Martin captures its essence as:

anything that people say or do that is perceived as funny and tends to make others laugh, as well as the mental processes that go into both creating and perceiving such an amusing stimulus, and also the affective response involved in enjoyment of it. (2007, p. 5)

Why Do We Produce Humor?

There is no shortage of benefits that humor may have conferred on our ancestors. Dozens of evolutionary hypotheses of humor have been proposed (for reviews see Martin, 2007; Polimeni & Reiss, 2006; Schmidt & Williams, 1971; Tisljar & Bereczhei, 2005; Vaid, 1999). Most accounts fall into one of ten categories. Humor is variously hypothesized to have evolved to: (1) promote social bonding (Dunbar, 1996; Dunbar et al., 2011); (2) facilitate cooperation (Jung, 2003); (3) disable pursuit of counterproductive paths (Chafe, 1987); (4) signal that a stimulus is non-threatening (Hayworth, 1928; Ramachandran, 1997); (5) signal interest in pursuing and maintaining social relationships (Li et al., 2009); (6) promote social learning (Fredrickson, 1988; Gervais & Wilson, 2005; Weisfeld, 1993); (7) manipulate status (Alexander, 1986; Pinker, 1997); (8) make finding and fixing inference errors fun (Hurley, Dennett, & Adams, 2011); (9) court mates (Miller, 1997; 2000); and (10) signal shared knowledge, attitudes, and preferences (Flamson & Barrett, 2008). These theories vary widely in their theoretical coherency, aspects of humor accounted for, falsifiability, and empirical support. The last theory is particularly well fleshed-out and relevant to the present discussion.

Humor as a Cue to Shared Common Knowledge

Although numerous theories of humor’s function have been put forward over the last two decades, only recently has an evolutionary perspective on humor’s origin also shed light on what makes something funny. Conventional wisdom has long held that we find things funny because we find them to be true. The “it’s funny because it’s true” premise is commonly used by stand-up comedians (Clarke, 2010, p. 86). Jerry Seinfeld’s “Have you ever noticed …,” and Jeff Foxworthy’s “You might be a redneck if…,” are observational forms of comedy predicated on the audience seeing the “truth” in the comedians' perspectives. According to evolutionary anthropologists Tom Flamson and Clark Barrett’s (2008) encryption theory of humor, shared background knowledge (conceptions of what is true) is central to humor production being appreciated.

In a successful joke, both the producer and the receiver share common background knowledge – the key – and the joke is engineered in such a way (including devices like incongruity) that there is a nonrandom fit between the surface utterance and this background knowledge that would only be apparent to another person with the background knowledge. Humor therefore guarantees or makes highly likely that specific, hidden knowledge was necessary to produce the humorous utterance, and that the same knowledge is present in anyone who understands the humor (Flamson & Barrett, 2008, p. 264).

Humor can thus serve as a means of assessing the shared underlying knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of others and “works, in a sense, as a mind reading spot-check, ‘pinging’ various minds in the environment and discovering those which are most compatible” (Flamson & Barrett, 2008, p. 266). Ancestral humans could have used reactions to humor in their attempts to assort on shared attitudes, interests, backgrounds, and goals, which would have allowed like-minded individuals to better form successful cooperative alliances and accrue the myriad fitness benefits that flow from them.

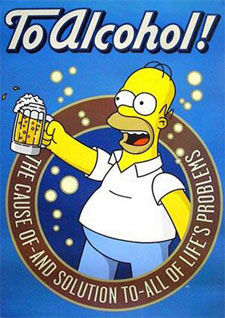

As Lynch (2010) notes in his nifty test of the “because it’s true” perspective on humor, one reason some find Homer Simpson’s toast funny is because they share with Homer the sobering awareness that alcohol can be used to escape from hardships that alcohol itself gave rise to (Groening, 2004). In this study, Lynch had participants watch 30-minutes of stand-up, scored their laughter using the facial action coding system, and measured their preferences using computer-timed Implicit Association Tests. As predicted, students laughed more at the specific bits that matched their implicit preferences. What they found to be true they found to be funny. Experiments by Flamson and Barrett (2008) showing that prior familiarity with a joke’s topic plays an important role in perceiving the joke as humorous also support the perspective that something is funny because it is true. It appears that, unless you’re The Most Interesting Man in the World, you’re unlikely to have inside jokes with complete strangers unless they share the requisite background knowledge that underlies the joke.

The Evolutionary Origins of Chris Rock’s Humor

The universal truth inherent in much of Chris Rock’s humor may be one reason for his phenomenal success as an entertainer. Although best known as a stand-up comedian, Rock is also an actor, author, screenwriter, director, and producer. His first HBO comedy special debuted in 1994 and his fifth aired in 2008. He was voted the fifth best stand-up comedian ever by the U.S.’s Comedy Central in 2004 and the eighth best by the U.K.’s Channel 4 in 2010 (Chris Rock, n.d.). Rock has won four Emmy Awards and three Grammy Awards. He has been called "probably the funniest and smartest comedian working today" by The New York Times (James, 1997), “the funniest man in America" by Time magazine (Farley, 1999), and was selected as one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People in the World in 2008 (Time 2008 Top 100).

Much of Rock’s riffs on sex and marriage ring true and hence funny with his audiences because he deftly evokes their understanding of evolved sex differences in human mating strategies (Buss, 2003). Rock’s ability to induce laughter by shining a comedic light on humans' universal nature is evidenced in the cross-cultural appeal of his most recent, Emmy Award winning HBO special, Kill the Messenger, which director Marty Callner spliced together from Rock’s performances in London, U.K., Harlem, U.S., and Johannesburg, S.A. Before unpacking the evolutionary theory and empirical evidence underlying 22 bits on human mating from Rock’s five HBO comedy specials, three disclaimers are warranted.

First, to preserve their artistic integrity and humor, unedited clips and transcriptions of relevant portions of Rock’s bits are used, and these often include profane, sexist, NSFW language. As a bit’s funniness is in part a function of its content and its delivery, it is important to render Rock’s riffs as he delivered them. Amending Rock’s humor by sanitizing it would threaten its funniness and undermine a central tenet of my main thesis (Chris Rock is funny because he evokes our evolved psychology). Additionally, sanitizing his humor by omitting or obscuring vulgar words smacks of snobbery and elitism. Surely we are not so precious that we cannot allow our scholarly minds to encounter the real life comedy that people around the real world find really funny. Moreover, sanitizing Rock’s bits by omitting or obscuring profane language with $&!% or f--k is uglier than the words themselves. Quite ironically, such devices serve to highlight the inclusion of forbidden words as the “words” now pop-off the page. There is no reason to draw any unnecessary attention to his use of profanity. Worse still, such devices unnecessarily tax the reader by purposely making sentences less intelligible.

Second, discussion of Rock’s material and the theory and evidence in support of his contentions are in no way whatsoever an endorsement or excuse for the behavior described. As has been thoroughly discussed by Pinker (2002), to conclude that something evolved or natural is inherently acceptable or permissible is to commit the naturalistic fallacy, and is, quite simply, moronic. (See my previous blog for an example of how gender feminists frequently commit this fallacy.)

Third, although a sure-fire way to ruin a joke is to explain it, that risk is knowingly undertaken here. Mining Rock’s humor for its reflections of human nature may dampen its comedic value, but I have succeeded if its intellectual underpinnings are laid bare.

The bits I’ll discuss here and over the next few blogs were selected because they illustrate mating domains explored by evolutionary psychologists that coincide with the various stages of many romantic relationships. As many mateships begin, I begin with a bit on opposite-sex friendships, before proceeding to discuss routines on mate preferences and mate attraction tactics. Subsequent blogs will flesh-out Professor Rock’s musings on conflict between romantic partners, parenting, infidelity, and divorce.

Opposite Sex Friendships

Women get to have platonic friends. "He’s my pal, he’s my bud. He’s my platonic friend, I love him like a brother. He’s my bud, my platonic friend!" Men don’t have platonic friends, ok? We just have women we haven’t fucked yet! "As soon as I figure this out, I’m in there!" We got some platonic friends. Oh no, I got some, but they all by accident! Every platonic friend I got is some woman I was trying to fuck, I made a wrong turn somewhere, and ended up in the friend zone. "Oh no, I'm in the friend zone!" (Rock, 1996, 42:10 - 43:00)

This perspective on opposite-sex friendship (OSF) is a common one in popular culture, perhaps most famously summarized by Billy Crystal’s character in When Harry Met Sally…: “Men and women can't be friends because the sex part always gets in the way” (Reiner, 1989). Research by Bleske-Rechek and Buss (Bleske & Buss, 2000; Bleske-Rechek & Buss, 2001) revealed the underlying kernel of truth in this overgeneralization: Relative to women, men rate sexual attraction and a desire for sex as more important reasons for initiating OSFs. Compared to women, men report a stronger preference for sexual attractiveness when initiating an OSF and rate the lack of sex as a more important reason for dissolving an OSF.

Mate Preferences

Whatever you into, your woman gotta be into too, and vice versa, or the shit ain't gonna work. It ain't gonna work. That's right. If you born-again, your woman gotta be born-again, too. If you a crackhead, your woman gotta be a crackhead too, or the shit won't work. You can't be like, ''I'm going to church, where you going?'' ''Hit the pipe!'' That relationship ain't going nowhere. But two crackheads can stay together forever. (Rock, 1999, 56:18 - 56:50)

Opposites may attract, but birds of a feather that flock together stay together. To maximize the likelihood that a couple can thrive long enough to reproduce and raise offspring, natural selection fashioned preferences for like-mindedness in a potential mate. Choosing a partner who has similar values, beliefs, and personality traits reduces conflict and the possibility of incompatible goals (Buss, 1985, 2003). Couples mismatched on these dimensions break-up more readily than those who are aligned (Hill, Rubin, & Peplau, 1976). However, one realm in which men do not necessarily prefer like-mindedness in a potential partner concerns promiscuity:

Guys, never ask a woman how many men she’s slept with. ‘Cause you don’t wanna know. Just be happy you’re fucking her now. . . . First of all, no matter what she say, it’s too much for you! No matter what she say, she can go, "Two," you be like, "Two?! Two?! Two?! No, no, no, two?! Two?! I guess that’s how you was raised!" (Rock, 1996, 44:24 - 45:08)

Men are acutely concerned with a mate’s sexual fidelity. Due to internal female fertilization, “a partner’s sexual infidelity puts men but not women at risk of incurring cuckoldry costs that include furthering another’s genes, losing a partner’s reproductive resources, wasted effort devoted to selecting, attracting, and courting a partner, and lowered status and reputation” (Kuhle, Smedley, & Schmitt, 2009, p. 500). As women’s past sexual proclivities can predict their future sexual sensibilities, promiscuity is a huge turn-off for men seeking a potential long-term mate, something women realize and attempt to mitigate with creative accounting:

Women will lie. . . . Women will lie about how many guys she fucked in court. They don't care. . . . Yo, if she says three, that's ten. You gotta give every woman like a seven dick curve. . . . And women, y'all think y'all are slick. Y'all ain't slick. I know the game, I watched it unfold. You ask a woman how many guys she's fucked, she's not gonna tell you how many guys she fucked, she tell you how many boyfriends she's had. 'Cause women only count their boyfriends. That's right, they don't count all those miscellaneous dicks they had. Ya know that guy they met at the club. . .or that time they fucked Bobby Brown. Or the guy they fucked in Jamaica; that's another country, it don't count. "I thought we just talking about domestic dick." (Rock, 1996, 45:10- 46:10)

However, sexual experience is not always a turn-off for men. As a means of solving the adaptive problem of identifying sexually accessible women (Buss & Schmitt, 1993), men pursuing a short-term mating strategy are drawn to women with ample sexual experience (Schmitt, Couden, & Baker, 2001), as Rock implies he is:

I love going to abortion rallies to pick up women. 'Cos you know they'll fuck you. You ain't gonna find a bunch of virgins at the abortion rally. . . . "What you doing here, girl?" "Fucked up again." (Rock, 1994, 41:44 - 42:10)

Mate preferences clearly vary as a function of the mating strategy pursued. They also vary as a function of one’s mate value. As women age, their mate value declines (Symons, 1979) and they are often forced to become less exacting in their preferences. For example, relative to their higher mate-value counterparts, less desirable women’s personal ads specify shorter lists of traits desired in a partner (Pawlowski & Dunbar, 1999). A 29-year-old Rock purports to exploit this shift in women’s standards as they age:

I like older women. I'm into older women. Ya know, not Weezy Jefferson old, just older than me. 'Cause young girls are full of shit. They like what they like. "So I want him to be this tall, want his hair to be like this, want his eyes to be like this, want him to walk like this, talk like this, work here." All this bullshit that has nothing to do with here [points to heart] and here [points to head]. Now you get an older woman, single, and she's like, "Hey, I just want to mate. He got a dick and a job, I'm happy." (Rock, 1994, 18:10 - 19:09)

Mate Attraction Tactics

Declining mate value aside, women in general are quite discerning in their mate preferences. And generally speaking, women’s and men’s mate preferences are similar. But in domains in which they recurrently faced different adaptive problems, different adaptive preferences have evolved (Buss, 2003). One realm in which women’s and men’s preferences diverge concerns resources. “The evolution of female preferences for males offering resources may be the most ancient and pervasive basis for female choice in the animal kingdom” (Buss, 2012, p. 109). Cross-culturally and cross-generationally, women value good financial prospects in a long-term mate about twice as much as men do (Buss, 1989a; Buss, Shackelford, Kirkpatrick, & Larsen, 2001). Women’s stronger preference for resources renders its accrual and display more important for men when attracting mates:

Men, you must get your money right. . . . It is important for men to get their money right. Women, it is important for you to get your money right, but it is not as important for you, as it is for us. Why, women? 'Cos no one will ever not fuck you 'cos you're broke. Your pussy will never be turned down for financial reasons. It ain't gonna happen. That's right, pussy's like VISA: accepted everywhere. Next time you don't got no cash, go, "Do you take pussy?" "Of course we take pussy. Who doesn't take pussy? How much pussy you got?" (Rock, 2008, 56:19 - 57:10)

Resources are central to a man’s mate value, a point Rock’s character’s boss makes to him in I Think I Love My Wife: “You know, Cooper, you can lose a lot of money chasing women. But you'll never lose women chasing money” (Rock, 2007, 52:39 - 52:46). Rock is keenly aware that his resources attract women:

Women see me, occasionally they wanna fuck me, but when women see me and they wanna fuck me they get real practical about it. Women go, "You know what? I bet you if I fucked Chris Rock, I could get him to pay my VISA bill." I have paid so many college loans in my day. I have put more girls through school than the United Negro College Fund! Shit, I should have my own dorm at Howard. (Rock, 1994, 1:08:56 -1:09:48)

Another dimension upon which men’s and women’s mate preferences diverge is physical appearance. Cross-culturally and cross-generationally, men rate physical attractiveness as being significantly more important and desirable than do women (Buss, 1989a; Buss et al., 2001). This sex difference exists because in ancestral times, women’s but not men’s looks served as honest signals of their reproductive value and fertility. In modern times, this is not always the case:

Masters of the lie, the visual lie. Look at you. You got on heels; you ain't that tall. You got on makeup; your face don't look like that. You got a weave; your hair ain't that long. You got a Wonderbra on; your titties ain't that big. Everything about you is a lie, and you expect me to tell the truth? Fuck you! (Rock, 1999, 53:14 - 53:41)

Rock Brings the Funny Because He Brings the Truth

From his 1996 classic Bring the Pain to his 2008 Emmy Award winning Kill the Messenger, Rock continually brings the funny because he always brings the truth. A truth his audience shares because they, like he, have inherited millions of years of evolved wisdom from ancestors long forgotten. Rock is able to connect with audiences around the globe because much of his humor taps into universal desires and fears that have sustained Homo sapiens for thousands of generations. Although Rock dedicates much of his stand-up to riffs on race, class, and politics, he closes each of his 5 HBO specials with evolution-grounded relationship humor. He seems to know that this, his best material, has broad appeal that reaches back through the eons and will bring his audience back in the future.

Speaking of coming back in the future, please drop by again soon for subsequent posts (Part II, Part III) that will discuss Rock’s theoretically sound, empirically supported, and downright hilarious riffs on conflict between romantic partners, parenting, infidelity, and divorce.

Follow me on Facebook and Twitter.

Sources: Portions of this blog were drawn directly from Kuhle, 2012.

References

Alexander, R. D. (1986). Ostracism and indirect reciprocity: The reproductive significance of humor. Ethology & Sociobiology, 7, 253-270.

Bleske, A. L., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Can men and women just be friends? Personal Relationships, 7, 131-151.

Buss, D. M. (1985). Human mate selection. American Scientist, 73, 47-51.

Buss, D. M. (1989a). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses testedin 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 1-49.

Buss, D. M. (2003). The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating (Revised edition). New York: Basic Books.

Buss, D. M. (2012). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind (4th ed.). Boston,MA: Pearson.

Chafe, W. (1987). Humor as a disabling mechanism. The American Behavioral Scientist, 30, 16-26.

Chris Rock (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 29, 2011 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chris_Rock

Clarke, A. (2010). The faculty of adaptability: Humour’s contribution to human ingenuity.Cumbria, UK: Pyrrhic House.

Cornwell, E. R., Palmer, C., Guinther, P. M., & Davis, H. P. (2005). Introductory psychologytexts as a view of sociobiology/evolutionary psychology’s role in psychology. Evolutionary Psychology, 3, 355–374.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: Murray.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1996). Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Dunbar, R. I. M., Baron, R. Frangou, A., Pearce, E., van Leeuwen, E. J. C., Stow, J., Partridge,G., MacDonald, I., Barra, V., & van Vugt, M. (2011). Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. Advance online publication. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1373

Farley, C. J. (1999, September). Seriously funny. Time. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,30524,00.html

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300-319.

Gervais, M., & Wilson, D. S. (2005). The evolution and functions of laughter and humor: Asynthetic approach. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80, 395-430.

Groening, M. (2004). The Simpsons. Los Angeles, CA: Fox Television.

Hayworth, D. (1928). The social origin and function of laughter. Psychological Review, 35, 367-384.

Hill, C. T., Rubin, Z., & Peplau, L. A. (1976). Breakups before marriage: The end of 103 affairs. Journal of Social Issues, 32, 147-168.

Humor. (n.d.a). In Oxford english dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/89416

Humor. (n.d.b). In Urban dictionary. Retrieved from http://humor.urbanup.com/1936108

Hurley, M. M., Dennett, D. C., Adams Jr., R. B. (2011). Inside jokes: Using humor to reverse-engineer the mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

James, C. (1997, February 10). Wicked, yes, but not mean-spirited. The New York Times, p C14.

Jung, W. E. (2003). The inner eye theory of laughter: Mindreader signals cooperator value. Evolutionary Psychology, 1, 214-253.

Li, N. P., Griskevicius, V., Durante, K. M., Jonason, P. K., Pasisz, D. J., & Aumer, K. (2009). An evolutionary perspective on humor: Sexual selection or interest indication? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 923-936.

Lynch, R. L. (2010). It’s funny because we think it’s true: Laughter is augmented by implicit preferences. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 141-148.

Martin, R. A. (2007). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Miller, G. F. (1997). Protean primates: The evolution of adaptive unpredictability in competition and courtship. In A. Whiten & R. W. Byrne (Eds.), Machiavellian intelligence II: Extensions and evaluations (pp. 312-340). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, G. F. (2000). The mating mind: How sexual choice shaped the evolution of human nature. New York: Doubleday & Co.

Pawlowski, B., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1999). Impact of market value on human mate choice decisions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 266, 281-285.

Pinker, S. (1997). How the mind works. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Polimeni, J., & Reiss, J. P. (2006). The first joke: Exploring the evolutionary origins of humor. Evolutionary Psychology, 4, 347-366.

Ramachandran, V. S. (1998). The neurology and evolution of humor, laughter, and smiling: The false alarm theory. Medical Hypotheses, 51, 351-354.

Reiner, R. (Producer & Director). (1989). When Harry Met Sally… [Motion Picture]. United States: Columbia Pictures.

Rock, C. (Executive Producer). (1994). Chris Rock: Big Ass Jokes [DVD]. HBO. Available on the DVD of Chris Rock: Never Scared.

Rock, C. (Executive Producer). (1996). Chris Rock: Bring the Pain [DVD]. DreamWorks Records Home Video.

Rock, C. (Executive Producer). (1999). Chris Rock: Bigger & Blacker [DVD]. HBO.

Rock, C. (Executive Producer). (2004). Chris Rock: Never Scared [DVD]. HBO.

Rock, C. (Producer & Director). (2007). I Think I Love My Wife [Motion Picture]. United States: Fox Searchlight.

Rock, C. (Executive Producer). (2008). Chris Rock: Kill the Messenger - London, New York,Johannesburg [DVD]. HBO.

Schmidt, H. E., & Williams, D. I. (1971). The evolution of theories of humour. Journal of Behavioral Science, 1, 95-106.

Silverman, I., & Fisher, M. (2001). Is psychology undergoing a paradigm shift? Past, present and future roles of evolutionary psychology. In S. A. Peterson & A. Somit (Eds.), Evolutionary approaches in the behavioural sciences: Towards a better understanding of human nature (pp. 203-216). NY: Elsevier.

Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. New York: Oxford.

The Time 2008 Top 100: The world's most influential people: (2008). Time Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/article/0,28804,1733748_1733752_1734626,00.html

Tisljar, R, & Bereczkei, T. (2005). An evolutionary interpretation of humor and laughter. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology, 3, 301-309.

Vaid, J. (1999). The evolution of humor: Do those who laugh last? In D. H. Rosen & M. C. Luebbert (Eds.), Evolution of the psyche (pp. 123-128). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers / Greenwood Publishing.

Webster, G. D. (2007a). Evolutionary theory’s increasing role in personality and social psychology. Evolutionary Psychology, 5, 84-91

Webster, G. D. (2007b). Evolutionary theory in cognitive neuroscience: A 20-year quantitative review of publication trends. Evolutionary Psychology, 5, 520-530

Weisfeld, G. E. (1993). The adaptive value of humor and laughter. Ethology & Sociobiology, 14, 141-169.

Copyright © 2012 Barry X. Kuhle. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the views of Psychology Today and the University of Scranton, or my friends, family, probation officer, gut bacteria, darkest thoughts, and personal mohel.